I've recently been rediscovering my love of interactive fiction, a formative medium for me when I was growing up.

A Brief Intro to Interactive Fiction

Interactive fiction (IF) includes several different classifications of thing, but usually the term refers to text-based (though not necessarily exclusively text) software games or stories which allow players to have some amount of control over how and/or when the story unfolds. There are two main styles of IF: choose your own adventure (CYOA) style, which offers a limited number of options that you can click on (similar to the old Choose Your Own Adventure books, which had you make decisions by flipping to a particular page), and parser IF, which allows you to type in the actions you want to take within the narrative. Some interactive fictions are more focused on telling a story, while others are more focused on creating a game experience (solving puzzles, winning).

|

Screenshot from CYOA style game Birdland, by Brendan Patrick Hennessy. Surprisingly, unrelated to my Fiction and the Historical Imagination course.

|

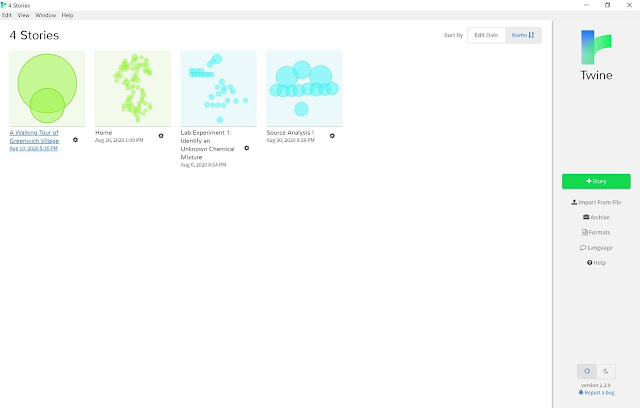

Before recently, I had never really tried to make my own games, content to play others (almost entirely parser IF); however, more recently I've been working on a few personal projects in the CYOA style. In this post, I want to talk about a couple of ways to use a tool often used for creating CYOA-style interactive fiction in the classroom: Twine.

Make Your Own Adventure

When I sat down to write this post, I thought that I'd talked before here about using Twine for history courses, but it turns out that I've only briefly mentioned the beginning of the Western unit. So, I'll preface this by saying that I've used Twine before in the classroom, assigning students to make their own takes on the Western genre which incorporated gamified or choice elements. Twine is a great tool for this sort of thing because it is very easy to learn enough to get started making a narrative. My Fiction and the Historical Imagination students used Twine for a "hackathon," spending the whole of a 50-minute class period putting together their games in small groups, and did a fantastic job embracing, challenging, and pushing the limits of the Western genre.

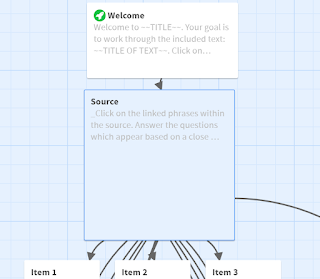

So, Twine can pretty easily be used as a student assignment tool. However, there are also ways in which instructors can make something in Twine to assign to students. Here's one example that works well for history: source analysis, especially close readings of shorter texts. So, being curious about how this might look, I knocked out a potential example, which you can experiment with either in the embedded version below or directly on itch.io.

"Source Analysis I" (a creative title right up there with my childhood stuffed animals "Lamby" and "Mr. Bear") took me about an hour and a half, not counting all of the other distractions I got up to along the way like changing the wording around, taking screenshots for this post, and testing it on a variety of devices and browsers. The goal is for students to click on the parts of the text that are linked to questions related to that phrase or idea, and answer the corresponding questions. As you may notice, this version of the activity offers students the option to collect their answers in their own document and turn that in, or type their answers directly into text boxes under each question; the answers are then returned to them all together at the end in a single page that can be emailed, printed, or submitted to an LMS. One could also assign only one or the other format; I wanted to include both in this activity to illustrate that there are multiple options for doing this sort of activity (and you can offer all, some, or only one to your students directly), and that one takes almost no "coding" and the other only minimal coding.

How much coding, you ask? In part II, I'll walk through the process of creating the activity, and talk more about the limitations of this particular version and of Twine overall. For now, though, I'll leave you with some of the...

Benefits of this activity

One of the things that can often be difficult about reading for college courses is figuring out how, exactly, you are supposed to read something. In history courses, we often want students to skim the textbook and pay close attention to the details of a primary source, but it can be difficult to explain and emphasize this distinction in a way that feels natural. I like that rendering a passage in Twine this way, with particular segments linked to related questions, makes the act of close reading feel more intentional, and the source as a whole a bit less daunting. Selecting a particular phrase and digging deeply into it becomes a more finite undertaking; it is no longer a long sheet of questions but rather a series of small tasks directly embedded into the text itself.

This version is a bit handholdy, suitable for an introduction to this sort of close reading. One could climb a bit higher on Bloom's Taxonomy by asking one or more follow-up questions; I like the idea of asking a student what segment of the text they would highlight and questions they would add if they were going to edit the game themselves.

I'll be back with part II soon, with a detailed walkthrough of how to make a similar activity. If there are any particular questions or features you'd like me to address, feel free to drop them in comments!

Related links:

If you want to try

playing interactive fiction yourself, the Interactive

Fiction Database (IFDB) is a great place to start. (You might find this friendly

beginner list or this other friendly

beginner list useful.

The Interactive Fiction Archive might be of

interest to digital humanists/technology historians.