Office Hours:

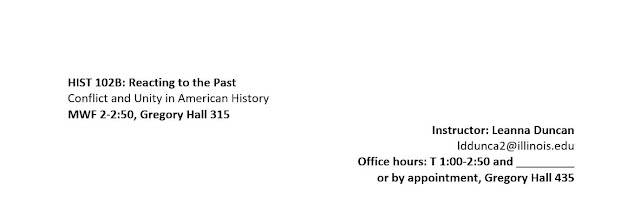

For instructors: As I mentioned last week, office hours can be a source of frustration when it seems as though no one knows you have them or when they are. You may consider doing something that I tried out last year: having one set of office hours you establish at the beginning, and letting students give feedback on when the second set would be. To do this, I structured the top of my syllabus like so:

Office hours can also be frustrating in other ways. When I taught Reacting to the Past: Conflict and Unity in American History the first time, we were in a classroom in the same building as my office. Students preparing for future sessions of a Reacting game frequently wanted to chat with me about their objectives, their assignments, and the historical context that might help them win. They frequently wanted to do this after class, and it was easy to oblige them even if the classroom was in use the next period-- we simply migrated up the stairs like a gaggle of birds alighting in a tree. That worked so beautifully that of course the next semester I was placed in a room across the quad, which completely changed how I could hold meetings with students. The lack of familiarity with the location of my office led to fewer people coming to office hours. If this happens to you, you might consider getting very specific with the location of your office on the syllabus, walking everyone to the building if it's not too far away, or scheduling early group or one-on-one meetings in your office to make sure everyone knows where it is and what to expect once they get there.

For students: Again, as I said last time, there are fully one hundred different advice documents for college students which urge them to go to office hours. I won't argue with that advice nor simply echo it, but I will give you a few tidbits which might help you use that time more effectively.

- You don't have to have a fully formed thought, though you should come with a topic in mind.

- It will help you to do this before you even start worrying about the paper. Often office hours are crowded when the paper is due because people are seeking advice on drafts, which is great! However, if you come to your instructor with your half-formed thought or question two weeks in advance of the paper, it is highly unlikely that you will leave that room without hearing "you could address this in your paper" at least once. That discussion will make the planning and writing process a lot easier and may save you some hasty last-minute revisions if you discover that, for example, you used a source to talk about World War I that is actually about World War II (Hey, it happens to the best of us).

- We often make quizzes, tests, and paper assignments based on what we think people are interested in or are thinking about. We often steer review sessions or top-of-the-hour explanations of topics towards questions we have received from people in the class. One of the ways we gauge these things is by what people ask about in office hours.

- If you can't come to office hours, don't be afraid to make an appointment. Most instructors are happy to do so-- as long as you actually show up.

Images (usually front and center on the first page):

(This section presented in the irresistibly imitatable style of David Ives' Sure Thing.)

For instructors:

"Look at these beautiful images, so lovingly presented! They will sure fill up some space on this page!"

(Bell.)

"They will sure make the students think my course is fun!"

(Bell.)

"These really capture the spirit of the course and serve...pedagogical ends?"

(Tense silence.)

For students:

"Someone designed this in color, and then printed it in black and white. Is this.. a lady? A building? I can't tell what it is. So, where's the section on grading?"

Grading /Grade Scale:

For instructors: This is perhaps the section I take the least amount of pleasure in making. I want it to be clear to students, meaningful to the course itself, and possible to calculate-- features which are harder to harmonize than it might seem. Give your later self a gift-- keep this section as simple as possible. Sure, you could have "In-class writing," "Quizzes," and "Participation" as three separate categories. But you could also just put them all under the umbrella of "Participation" and explain that this category is made up of several different kinds of work. This isn't to say that you can never separate things out-- if you think that quizzes are particularly important to emphasize and want to make them their own category, do so! It will help if you really consider what themes and skills you want to emphasize in the course. If you are interested in promoting writing skills, writing assignments should take a sizable portion of the grade; if you are more focused on encouraging students to engage with the material at their own pace, participation might be more central to your calculations. Keeping things both simple and meaningful will help you at the end of the semester when you are calculating grades and realize that somewhere amidst all the percentages you've lost the plot.

For students: For some of you, this is the first place you look; for others, you will only try to make sense of it as the semester winds up and you try to figure out what you should have in the course. As I've implied above, most of us don't find great passion in figuring out the grade breakdown, so try to look beyond the rigidity of the numbers and figure out what they mean. For example:

For instructors: "Wait, did I forget to account for Labor Day?" If you are including a schedule in your syllabus, you could easily spend half of the writing time trying to get the dates right. I have no fresh and handy tips on this horrible process. Godspeed.

For students: This is probably the most critical part of the syllabus for your purposes, because as I'm sure you've heard roughly one million times by now, no one will remind you about due dates in college. (This is not exactly true. Everyone I know reminds students about due dates a lot, at least for big assignments). More significantly, then, the schedule lets you know what you're supposed to be reading for each meeting, and this is something that you will likely not get reminded on every week-- assume that there's always reading, and that it's on the syllabus, and that someone will tell you if that's not the case. It's easy to develop a sort of tunnel vision for the schedule-- what is the very next thing I have to do?-- but try to find some time between week one and week two to glance over the whole thing and see if you can get a sense of the arc of the course in terms of themes, assignments, and readings. Is the course moving chronologically? (Probably.) If so, you know roughly what book you will need at what time. When is the first paper due? The timing will give you an idea of the probable topics for the paper. Getting a sense of how things are arranged makes moving through the course easier.

Final Thoughts:

There are, of course, lots of other sections that can appear on a syllabus-- accessibility/ accommodations statements, policies on late work (which I've touched on a bit elsewhere), breakdowns of particular assignment types or pet peeves of the instructor.

Honestly, I end this piece not with some overarching advice or wisdom but with more questions. As I look back at old syllabi of my own from classes I've taught and taken, at syllabi posted online from classes at other schools, and at advice on crafting syllabi, I'm struck and somewhat dismayed by how forbidding in tone they can be. There's an element of fear to a syllabus, of self-protection. There's a lot of bolding and underlining, all caps instructions, and incredibly specific instructions, all likely there because there have been Incidents in the past. I'm not passing judgment idly here-- my syllabi also read as more combative than I would like. Interestingly, in graduate level syllabi many of the more defensive sections disappear, leaving the rationale, the calendar, and perhaps the grade scale. Is it possible to preserve the clarity of expectations that these undergraduate level syllabi embody without sounding quite so legalistic about it all? Are syllabi really "contracts" in addition to "road maps"?And if so, must a contract be written as though someone is trying to pull a fast one, or can it be a source of mutual comfort and protection?

Related Links:

Advice for instructors on maximizing office hours from U of I's LAS Teaching Academy.

"Sure Thing" appears in All in the Timing, along with the similarly multiple "Variations on the Death of Trotsky."

In addition to old syllabi of my own, the many history course syllabi on this site helped to jog my memory on common syllabus categories.

(This section presented in the irresistibly imitatable style of David Ives' Sure Thing.)

For instructors:

"Look at these beautiful images, so lovingly presented! They will sure fill up some space on this page!"

(Bell.)

"They will sure make the students think my course is fun!"

(Bell.)

"These really capture the spirit of the course and serve...pedagogical ends?"

(Tense silence.)

For students:

"Someone designed this in color, and then printed it in black and white. Is this.. a lady? A building? I can't tell what it is. So, where's the section on grading?"

Grading /Grade Scale:

For instructors: This is perhaps the section I take the least amount of pleasure in making. I want it to be clear to students, meaningful to the course itself, and possible to calculate-- features which are harder to harmonize than it might seem. Give your later self a gift-- keep this section as simple as possible. Sure, you could have "In-class writing," "Quizzes," and "Participation" as three separate categories. But you could also just put them all under the umbrella of "Participation" and explain that this category is made up of several different kinds of work. This isn't to say that you can never separate things out-- if you think that quizzes are particularly important to emphasize and want to make them their own category, do so! It will help if you really consider what themes and skills you want to emphasize in the course. If you are interested in promoting writing skills, writing assignments should take a sizable portion of the grade; if you are more focused on encouraging students to engage with the material at their own pace, participation might be more central to your calculations. Keeping things both simple and meaningful will help you at the end of the semester when you are calculating grades and realize that somewhere amidst all the percentages you've lost the plot.

For students: For some of you, this is the first place you look; for others, you will only try to make sense of it as the semester winds up and you try to figure out what you should have in the course. As I've implied above, most of us don't find great passion in figuring out the grade breakdown, so try to look beyond the rigidity of the numbers and figure out what they mean. For example:

- A high percentage given to participation (arguably, anything 20% or higher) means that discussion and engagement probably plays a big role in what the instructor wants the course to be. For some, this may mean they expect everyone to straight up speak to the group at least once per class; others take a broader approach to what participation is, including things like active listening and making space for less intense one-on-one discussions of material.

- History courses can vary widely in terms of assessment. Are there quizzes, tests, and essays, and how is each weighted? Quizzes can serve as a sort of gauge for attendance; they can be part of participation; they can stand alone as a small or large percentage category, Looking at the grade scale with an analytical eye will help you determine how much the instructor values each of these things and distribute your efforts accordingly. (It's also great practice for doing the actual work of historical analysis, which generally involves analyzing aspects of a document. Win-win?)

For instructors: "Wait, did I forget to account for Labor Day?" If you are including a schedule in your syllabus, you could easily spend half of the writing time trying to get the dates right. I have no fresh and handy tips on this horrible process. Godspeed.

For students: This is probably the most critical part of the syllabus for your purposes, because as I'm sure you've heard roughly one million times by now, no one will remind you about due dates in college. (This is not exactly true. Everyone I know reminds students about due dates a lot, at least for big assignments). More significantly, then, the schedule lets you know what you're supposed to be reading for each meeting, and this is something that you will likely not get reminded on every week-- assume that there's always reading, and that it's on the syllabus, and that someone will tell you if that's not the case. It's easy to develop a sort of tunnel vision for the schedule-- what is the very next thing I have to do?-- but try to find some time between week one and week two to glance over the whole thing and see if you can get a sense of the arc of the course in terms of themes, assignments, and readings. Is the course moving chronologically? (Probably.) If so, you know roughly what book you will need at what time. When is the first paper due? The timing will give you an idea of the probable topics for the paper. Getting a sense of how things are arranged makes moving through the course easier.

Final Thoughts:

There are, of course, lots of other sections that can appear on a syllabus-- accessibility/ accommodations statements, policies on late work (which I've touched on a bit elsewhere), breakdowns of particular assignment types or pet peeves of the instructor.

Honestly, I end this piece not with some overarching advice or wisdom but with more questions. As I look back at old syllabi of my own from classes I've taught and taken, at syllabi posted online from classes at other schools, and at advice on crafting syllabi, I'm struck and somewhat dismayed by how forbidding in tone they can be. There's an element of fear to a syllabus, of self-protection. There's a lot of bolding and underlining, all caps instructions, and incredibly specific instructions, all likely there because there have been Incidents in the past. I'm not passing judgment idly here-- my syllabi also read as more combative than I would like. Interestingly, in graduate level syllabi many of the more defensive sections disappear, leaving the rationale, the calendar, and perhaps the grade scale. Is it possible to preserve the clarity of expectations that these undergraduate level syllabi embody without sounding quite so legalistic about it all? Are syllabi really "contracts" in addition to "road maps"?And if so, must a contract be written as though someone is trying to pull a fast one, or can it be a source of mutual comfort and protection?

Related Links:

Advice for instructors on maximizing office hours from U of I's LAS Teaching Academy.

"Sure Thing" appears in All in the Timing, along with the similarly multiple "Variations on the Death of Trotsky."

In addition to old syllabi of my own, the many history course syllabi on this site helped to jog my memory on common syllabus categories.