|

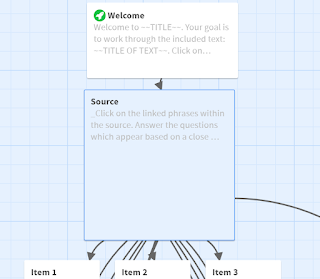

| I made this graphic in Canva. |

Recently I had

the pleasure of joining current and former graduate students from the UIUC Department

of History to discuss my experiences with career diversity and my embrace of a

non-tenure track career path. Teaching can play a critical role in that path,

as teaching is often (though not always) the first chance that many graduate

students get to apply their skills in a different way than their writing and

research, and to something that often feels like a space more within their

control and more akin to "paid employment" than other aspects of their lives and work.

Because of this

connection between teaching and career development, I wanted to reflect today on some takeaways of that session,

particularly since teaching is instrumental to that story. I've divided these into three key topics (as you may have guessed from the graphic): mindsets that in hindsight I found to be the most helpful things I did without always knowing that's what I was doing.

A note that most of these observations are for people thinking about their place on this path, not for the people who organize graduate programs, except insofar as those people might well take the idea from this to emphasize creating space and opportunity for these things to take place. The reason why is twofold; first, this was my experience, and I can speak to it better than just about anything else. Second, at the end of the day, I am fairly aware of who makes up my readership (friends, current and former graduate students, and some of my former students, hello!), and no one is more capable, more interested, or more qualified to make the kind of decisions I made, wish I made, wish I'd made more often and in more ways, than you are.

Take

Lots of people

talk about the "tenure-track academia" path and the "not

that" path as two separate ones, but there was really never a "two roads

diverged in the wood and I" moment for me.* During the course of our

conversation, I concocted a somewhat tortured but nevertheless illustrative

metaphor about the journey. For me, deciding to go to gradschool was a bit like

going to the store for apples. I knew that I was going to go in and come out

with apples-- or, as a professor. As I started moving through the aisles,

though, I started grabbing some other things, and realized by the end that I

had a basket filled with a lot of things, which I could use in service of a lot

of different goals. And every time I grabbed an extra thing to put in that

basket-- that is, developed a new interest, took on a job or volunteered to do

a task-- I didn't do it with a perfect grand plan in mind. It came from

following my interests, trying things that sounded interesting and that I

wanted to know more about. In short, you don't have to make a large decision to

pursue keeping your options open-- you just have to take things and put them in your basket, knowing they might give you options later.

Talk

Networking

isn't schmoozing, it's reciprocal and thus is tied with knowing the value of your labor. Alison Green has pointed this out in many ways on Ask a Manager, and

the topic came up in our conversation as well. When someone is in dire need of

a job, it can be hard for them to see the other person as a person rather than as an opportunity-dispensing machine. But most folks I know are actually interested in other people! So, approach your talk with mutual gain in mind. Most people love to know that something from their

experience helped you. And if you know the value of your labor, you'll know that it can incredibly helpful for someone to be able to say, soon or far in the future, "oh yes, I know someone who might be able to fill that position/consult on that work/ direct that project." But it probably isn't something they can do immediately-- networking in this way is setting yourself up for the potential future, just the way the opportunities you put into your grocery basket are. Most folks don't have the power to just pick you up and slot you into a job,

and if it worked that way it would be even more unfair than the process often is currently. It's like any other relationship you build with another

human: you can't rush trust, comfort, or intimacy. You have to build it with

small bits of evidence about your interests, skills, and work style.

That also means

networking doesn't have to be overly complicated or awkward. For me, networking

was volunteering a couple of hours of my life to keep time during the

university's teaching assistant orientation's microteaching sessions. It was

joining a professional organization in a field I was interested in and

attending a virtual event. It was scheduling a meeting with a graduate career advisor who introduced me to someone in a field I was interested in. It was doing a couple of informational interviews with various people

who were, uniformly, happy to talk to someone about what they do. Even the things

that I didn’t want to do, ultimately, were helpful. Some of the useful

information I got from informational interviews was "well, I don't want to

do that!" So, talk-- to anyone and everyone who knows something about something you think you might like to know more about.

Think

Teaching

skills-- like all skills-- can stand you in good stead in many markets, but you have to actually think about how you are doing it and why. Unfortunately,

many graduate students do not feel encouraged to do this reflective work, at

least in my experience and my conversations with others. They are instead told to go and do what is necessary to keep their

funding and get through the semester, but they are not encouraged to develop

pedagogically beyond what is "always done." As unfair as this may be,

this means that most have to use the opportunities they have to make this sort of

experience count through their own initiative, as rarely will anyone scaffold this particularly well for you. Going into class and telling students

"discuss the reading" will not provide useful experience for you; nor will putting lots

of effort into things without reflection, like painstakingly writing the same

three wordy comments on every essay.

This doesn't mean you need to agonize over every lesson or reinvent the wheel every time you open your Zoom window/classroom door/Canvas course. Instead, I suggest finding one topic, idea, or objective you want to emphasize the next time you teach and really think about how best to do so: do some research on how others have taught similar ideas, create a novel activity or assessment, and talk to your most pedagogically-minded colleagues about what you're planning, how it went, and what they do in their own courses. In doing so, you'll have created an example that you can forever use as an indication of your teaching style and your work style.

I hope take, talk, and think are as useful to you as they have been to me. And of course, you're always welcome to take from (the archives of Activities and Materials are open for your perusal!), talk to (contact info is on the right sidebar!), and think along with me.

Notes:

*Not especially a huge Robert Frost person,

but I always find myself quoting him in writing; just like experiences, I often

throw little bits of language that strike me into "my basket" for

later. (My favorite which I slipped into my dissertation is "Home

is the place where, when you have to go there,/They have to take you in.")

Plug and Play Miniseries Lesson Spotting with AI: Designing Prompts (but not like that)

Plug and Play Miniseries Lesson Spotting with AI: Designing Prompts (but not like that)

Take My Advice: If You Have Trouble With Tech

Take My Advice: If You Have Trouble With Tech