|

Signs in various languages indicating different locations.

Photo by Soner Eker on Unsplash. |

Today I have teamed up with a fantastic guest-poster. Logan Middleton is a PhD student in writing studies who works with the Education Justice Project, a college-in-prison program in Illinois. (You may remember him from my enthusiastic posts about his work as a workshop leader: Writing Across Curriculum and Staying on Track With Thesis and Dissertation Writing.) His words are in regular case throughout, and my contributions, largely about how these topics relate to particular types of classrooms and disciplines, are italicized.

What Price Grammar?

From my experiences in teaching writing, the number one thing I hear from students of all ages is “I’m a bad writer.” If I ask why and dig a little deeper, it’s usually because someone has been told as such by a former teacher. Dig a little more, and I hear refrains to the tune of “My English is bad” or “My grammar is bad.”

It’s not uncommon to hear from instructors or administrators that we need to ensure students can use “proper” English and grammar. Not only must we uphold “correctness,” they say, but we can’t conscionably let students go out into the real world with their writing looking like “that.”

Statements such as these hurt students. From my experiences as an instructor and as a tutor, they not only make them dislike writing but also make them afraid to write. I recall working with one first-year college student who, in introducing me to her assignment prompt, said to me, “I’ve been told by teachers that I don’t communicate very well.” Though I can’t speak for this particular student, I have a hard time imagining them as feeling excited or good about their work—in their first semester of college nonetheless.

The ideologies undergirding statements about proper English and correctness not only hurt students but the rest of us as well. This is in no small part because they’re racist. This isn’t a particularly new or novel idea; I’ll say more about it in a bit. But I want to stay with this idea of grammar and how it relates to writing, teaching, and English.

It’s striking to me that people who claim English as a first language can often tell that something is “grammatically incorrect.” I find myself in this position often. Less often can we explain with any certainty why that’s the case. I also find myself in this position a lot as do students. Oftentimes, the things native English speakers can identify as grammatical rules are based on outdated folk models of grammar that were handed down by family or teachers, the likes of which would hardly be recognized as legit by contemporary theories of language. So contrary to what we might think or believe, our ideas of what English grammar should look like aren’t really all that sound or accurate.

Intriguingly, this sort of knowledge or memory is often something historians feel like they are combatting in their courses, letting students know that what feels true about historical figures, places, and ideas is not always what is actually true. Good historians know that they fall prey to these same patterns of thinking even as they combat them; writing and grammar is an arena where we rarely think to look for such patterns.

All of this discussion about English and language and correctness matters because instructors who teach writing—many of whom have not been formally taught how to teach writing themselves (through no fault of their own)—are often concerned with assessing grammar in student work, especially when it comes to emergent bilingual or multilingual student populations. We know grammar is built upon sets of rules, but how can we enforce these standards in student work if we can’t even describe the mechanisms by which they operate? All of this becomes more problematic when instructors wield grammar as a tool of punishment in grading and feedback contexts, as a means of marking down student papers. Such logics operate in accordance with deviation from a set, centralized, universal standard of linguistic purity.

I find this particularly interesting in History because often it is very difficult to 1. Teach historical thinking and 2. Make a quick case about why historical thinking, specifically, is important. I often hear people make the case that history courses’ most critical contribution is to teach students how to write (okay, I have been guilty of emphasizing this myself at times). The more I teach, however-- and the more I learn about writing-- the more I question whether this is actually the core thing we do, and whether it is a worthwhile goal for historians in particular to do. Few instructors of history think it would be a worthwhile goal to spend several weeks on English grammar and syntax, yet they grade for these details. One takeaway here, then, is to clarify the central goals of your course-- what are you actually hoping that students take away from this course? If better writing is one of your goals, is it more critical that students follow your preferred grammar, or that they learn to organize their thoughts, or make a clear argument?

Against Purity

Linguistic purity is a guiding feature of Dominant American English (DAE) or White Mainstream English (WME). These varieties of English, of which grammatical correctness is a part, function as ideologies that fundamentally exclude rhetorical and linguistic traditions that aren’t white, western, abled, or middle-classed: African American Language, Spanglish, and neurodivergent communication, to name a few examples (see the work of Django Paris, Carmen Kynard, Steven Alvarez, Christina V. Cedillo, and others). And while some well-intentioned instructors might say, “It’s OK to communicate like that at home, but not in your writing for this class,” what this comment really says is, “You can write or speak like that at home, but you(r languages) are not welcome here.” We can’t pretend that we can separate language from identity since we know language is social and cultural in nature. As many students will show us if given the chance—whether they’re multilingual students or not—our language practices are part of who we are.

Whether we realize it or not, linguistic purity often goes hand in hand with racial purity. Those students whose language most gets targeted in writing contexts are likely students of color, many of whom are international students and/or multilingual students (though, of course, these identity categories are not mutually exclusive).

So when instructors claim that adhering to Dominant American English is preparation for the real world, I’m reminded of “I Can Switch My Language, But I Can't Switch My Skin" by the brilliant Dr. April Baker-Bell (a piece that students have responded really well to for the most part). Speaking of linguistic racism, she notes that communicating in WME doesn’t lead to guaranteed success for Black folx, it doesn’t prevent Black folx from being impacted by racism, and it certainly doesn’t help Black folx from being murdered.

As I’ve previously touched upon (though I am far from the first to so so), there are a myriad of ways in which the people who are supposed to be promoting progressivism or providing aid or combating inequity in some of their work shore it up in other arenas. Similarly, many academics shore up white supremacist and imperialist ideals of writing and classroom comportment even as they critique these frameworks in their research. Their day-to-day functions butt up against their ideals.

Disability scholar Sami Schalk contends academic work about people with disabilities exists that is not actually an example of "disability studies.” Disability studies, she contends, should be at its base for the benefit of disabled people as embodied and political actors. Work about disability or disabled subjects that does not do those things is disconnected from the field’s purpose. Similarly, there is a disconnect if we as teachers and scholars claim to be advocating for immigrants, people of color, people with disabilities, the subaltern, and/or the working class without also supporting the actual students from those communities by whom we find ourselves surrounded.

Linguistic Justice

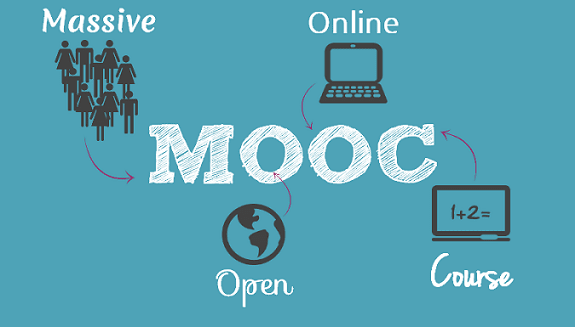

What’s this look like? For me, that means recognizing—and communicating to students—that academic language is a white, colonial, elite system of gatekeeping for people in power. It means making space for students to use their full linguistic repertoires in the classroom, to draw upon varieties of spoken and written languages in talk and text. And it means explicitly stating that language is not just linguistic in nature; it’s always entangled with visual, sonic, spatial, gestural, affective, and embodied communication.

As a writing instructor, I speak with students on the first day of class about my course’s language policy—shoutout to María Carvajal Regidor for her work in writing this policy, which I’ve tweaked a bit. It appears in full below.

“The ways in which people are socialized into White Mainstream English and Academic English are often violent, damaging processes for multilingual and non-multilingual individuals alike. As such, I’m open to and encouraging of student work that represents or draws upon students’ full linguistic repertoires. That is to say, if you know multiple languages or codes and want to use them—either in written work you submit or verbally in the classroom—I’ll engage your contributions just as seriously as I would engage with more mainstream or academic forms of English. If there’s anything I can do to be more supportive of your language needs, please do speak with me so I can better support you. At any point in the semester, feel free to ask me, either during office hours or in class, about how I’d respond to work that isn’t communicated in ways that are traditionally valued in university spaces.”

I’ve found it important to frame things here in terms of an invitation. Just because students know multiple languages and language varieties doesn’t mean that they necessarily want to use them in a classroom setting. And so creating opportunities for students to possibly take up such practices—on their own terms and in a way that works best for them—can be a productive way of addressing language diversity in teaching situations, at least from a curricular point of view.

Pedagogically speaking, I often invite students to interrogate their language histories, writing practices, and social identities by writing a critical linguistic autobiography. This assignment asks writers to take stock of the texts and contexts that shaped their language use and to address how their social identities shape how they use language. In the semesters I’ve used this assignment, students have written about affective interconnections between home, school, and Latinx identity; railed against gendered expectations about swearing in profanity-laced reflections; and blended autobiography with poetry in genre-bending mashups. Even for non-Black, non-brown, and non-POC students, this exercise can encourage students to think critically about how white (language) supremacy impacts dynamics of power when it comes to class, gender, sexuality, ability, and the manifold ways language is policed by others.

I’ll move to wrapping up here by returning to the issue of non-linguistic language as noted above. When we think of writing and language, English alphabetic text often comes to mind. But we’re always communicating beyond words—with image, talk, sound, movement, gesture, and affectively. Even though these forms of communication are critical in everyday life, they often go unrecognized as essential meaning-making practices. Such communicative practices are even more invalidated when performed by Black and brown populations (see Adam Banks and Geneva Smitherman) and disabled populations (see Melanie Yergeau) as well as other multiply minoritized people.

So if we want to better enact linguistic justice, we not only need to address white supremacy through discussions of language diversity but we’ve also got to push back on narrow, restrictive notions of language, literacy, and writing—the likes of which exclude a host of rich, communicative practices. One of my former colleagues, Katherine Flowers, employs a language policy similar to the one discussed above that invites students to compose their work in whatever modalities (visual, sonic, etc.) that make the most sense for their project’s aims. Such a move both grants students the chance to critically think through what languages and modes will help them accomplish what they’re hoping to accomplish. When I’ve taken this approach in my own teaching, students have created final projects that I’d never have even thought of, texts as communicatively diverse and imaginative as choreographed dances and 3D-printed objects. So how we regulate the modes in which we communicate, too, is also a matter of linguistic justice.

Historians as well as other humanists already have the classroom tools for students to contribute their own knowledge or experience, and many of us have realized how much allowing students to do so invigorates a room full of thinkers. Consider how sparkling class discussions become when a student contributes unique knowledge of a source. In a discussion from this past semester on a selection of the Padma Purana, one of my students used his personal experience with the larger text not only to give the class additional context, but in doing so shed light on how the source was interpreted in the modern day as well as when the text was written. It became a living document in a way that I did not have the ability to make it. We encourage students to bring in their experiences frequently, or at least, we should-- their experience of language should be no different.

Depending on your degree of teaching experience as well as what field you’re in, these steps toward teaching for linguistic justice might seem small or overwhelming, possible or inconceivable. In trying these strategies on, hopefully we can inch closer to a more just world—in our classroom and beyond.

Related Links:

Carmen Kynard’s website provides a range of scholarship, pedagogical resources, and commentary on race, writing, and teaching.