|

| Photo by Işıl via Pexels. |

In my last feature in this series, I talked about using GPTs to help in the process and clarification of your writing. This entry is a bit of a cheat in this series, since it doesn't actually involve prompting a GPT at all.

Good UX always inspires me to think about how to use some of these strategies more broadly. I remember being mildly affronted during the CITL reading group I attended when I first became interested in better teaching-- did I spend that whole several weeks affronted? Apparently! Clearly it was challenging me in some useful ways-- because one of the resources we read discussed using advertising principles to make learning "stick." Advertising? That soulless capitalist enterprise? Could help me teach the intellectually rigorous discipline of history? Pish-posh!

Of course, the only thing we do if we eschew these strategies is ensure that what they're learning in our class presently doesn't seem quite as memorable as literally any reasonably well-crafted local commercial they saw roughly a decade ago, which is what I eventually realized as I considered the concepts that were "sticky" in my brain and why.

With that in mind, you might reflect on ways that new tools introduce themselves to you, and see if that sparks an idea about how you might in turn introduce a concept that is very familiar to you in a way that seems approachable to a new learner. I'll use the original starting page for ChatGPT as an inspiration to explain something, such as instructions or expectations for an assignment. One thing that is inherently challenging is to explain something you know very well to someone else. It can be more challenging than explaining something you only know kind of well., as you have to identify the most significant information out of all the information you know and explain it clearly.

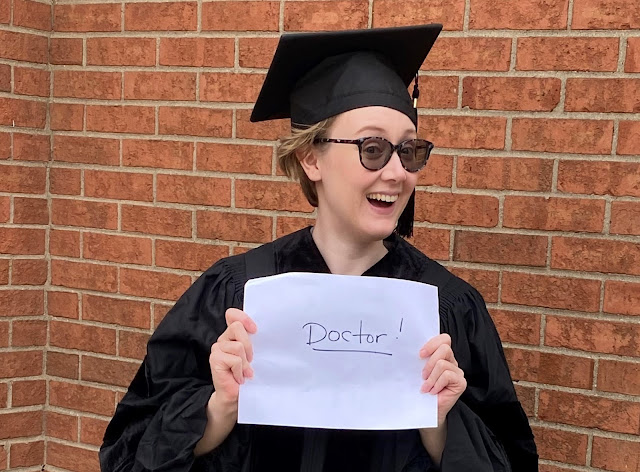

Let's take a look at how ChatGPT introduced itself when I encountered it (this has since changed as public familiarity with the tool has increased):

|

| Original ChatGPT intro screen. Image via Datamation. |

This screen introduces the tool by offering a breakdown of examples of things you could ask it ("Explain quantum computing in simple terms"), capabilities the tool has ("Remembers what user said earlier in the conversation"), and limitations the tool has ("May occasionally generate incorrect information.")

What if you tried a Examples, Capabilities, Limitations breakdown for assignment instructions? I've seen many, many pagelong or multipage prompts for a paper that's only 3-5 pages long. Rather than paragraphs of context and/or admonitions based on past experiences ("12 point font and 1.5 inch margins this time-- I'm talking to you, Bradley"), what might it look like to organize a prompt arount the following structure:

- Examples (of excellent work or strong approaches to the work),

- Needed Capabilities (of the deliverable students will produce),

- Limitations (or parameters they need to work within to produce this work)

Obviously a prompt doesn't have to stay in this format-- I'm not suggesting that the original ChatGPT welcome page cracked some kind of fundamental educational code. But instructions that you find clear or helpful in introducing you to a new topic may be useful in turn to incorporate into your own teaching strategies.