Happy New Year! In the general holiday spirit of making things better, I've created a guide to my post labels. I was inspired by writing this post to do so, as I realized that I think about the topic of student advice so frequently that I will probably want to write about it again.

Advice is a different category than the ostensible goals of many courses. It's not historical facts, which seems obvious; it's not really even just skills like writing or reading strategies, although it can encompass these things. Rather, I think of advice as information about how to approach things which students might not be tested on, but which may help them in both the course and their academic, professional, or personal lives. There are many informal online resources giving a wide variety of tips to college students, often written by professors or instructors, so I am clearly not alone in this impulse (and I should note here that these links are purely examples of the impulse, not support for all of the advice or language contained within). I think a lot about how to pass along things I've learned to students, probably because there are so many things I wish I had known earlier in my journey. I find myself wanting to give my students the advice that I never got, or was given but did not fully understand, when I was in their position.

There are many reasons to resist the impulse to advise. Most of those students will never be in my particular position-- the vast majority will not go on to pursue a graduate degree in history. And no one wants to be inundated with a barrage of helpful hints about life while in their 9 AM history class, regardless of their applicability to their own experiences. So, what advice is important enough to emphasize? And how do we incorporate advice into our classes, whether it be advice about history, academia, or life in general? I'll address questions of this sort under the "Take My Advice" label.

The first strategy I always want to impress upon students is the critical skill of communicating with one's instructors. This may sound very simple and very obvious and is indeed repeated by basically every instructor I've met, in varying forms but most often in the phrase "Come to office hours" and its followup, "No one ever comes to office hours." Both professors and graduate instructors encourage folks to come to their office hours frequently, but in most courses nonattendance by ninety-eight percent of the class is the norm. (My Reacting classes have been an exception to this rule, though the percentage is still less favorable than I would like.)

This is pretty easy to understand when I think back to my own undergraduate experience-- I did attend a few office hours and got a lot out of them, but for the most part I considered them a last resort for the desperately behind because it seemed so serious to seek out a professor in their private domain and discuss something one-on-one. It's very similar to how I feel about phone calls-- one must have Something To Say that is both specific and important to communicate. This is not to say that I want my students to show up and have nothing in particular to say ("Hi Teach! I plan to stare at you uncomfortably for fifteen minutes or so") but rather that office hours are a great time to develop understanding even without a particular "deliverable" on the table.

For example, taking fifteen minutes to ask questions about the reading or discussion that weren't fully clear during class is a worthwhile use of office hours, even if these questions don't apply directly to a current assignment. This isn't just because of "face time" or some similar nonsense-- it's because it both helps a student think through the material and help me figure out how they think. Like many instructors, I tend to base lectures and assignments in part on information I have gotten from the students. The first time I taught The Trial of Anne Hutchinson, I added a brief section on the Reformation to the lecture after it became clear on the first day of class that people wanted more context for the particular religious positionality of the Puritans. If I know what students are grappling with, I can tailor class time to addressing those questions. I can also base quiz and exam questions on topics they find particularly interesting or relevant.

For example, taking fifteen minutes to ask questions about the reading or discussion that weren't fully clear during class is a worthwhile use of office hours, even if these questions don't apply directly to a current assignment. This isn't just because of "face time" or some similar nonsense-- it's because it both helps a student think through the material and help me figure out how they think. Like many instructors, I tend to base lectures and assignments in part on information I have gotten from the students. The first time I taught The Trial of Anne Hutchinson, I added a brief section on the Reformation to the lecture after it became clear on the first day of class that people wanted more context for the particular religious positionality of the Puritans. If I know what students are grappling with, I can tailor class time to addressing those questions. I can also base quiz and exam questions on topics they find particularly interesting or relevant.

The idea of communication with an instructor extends beyond the idea of filling office hours, however. I also want to encourage students to approach me with accommodations or schedule modifications they need-- that is, to encourage communication more broadly. This is a critical part of treating college students as the adults they are and acknowledging that all people, by virtue of being human, occasionally need to adjust or negotiate the ways their time is allotted. Frequently, the complaint is voiced on the other side- that students do not respect instructors' time-- which can certainly also be true. I try to model respect for student time in the hopes that it will also encourage greater reflection on the value of others' time.

In a teaching-focused reading group I attended last year, I and the other participants debated the idea of taking off points for late assignments. This is a fairly electric issue-- although in my memory, we appreciated the text's point that punctuality has little to do with mastery of the material, per se, we also expressed an interest in protecting our own time, as grading assignments piecemeal tends to take much longer than doing them all together. Ultimately this conflict is often resolved with a communication compromise: If a student requests an extension in advance of the deadline, the delay does not affect their grade. This resolution promotes respect for the time of both parties, benefiting both. Encouraging students to approach me and, by extension, other instructors when they know they will be absent from an important meeting, need an extension, or have to reschedule an exam could result in a more convenient schedule if one isn't trying to complete two projects at the same time when they could have received an extension for one. It could also result in an improved grade, if it frees a student from trying to plow through the project without careful thought simply to get it in on time. And even if discussion with an instructor does not lead to an extension, it will at least lead to greater clarity on what the instructor's expectations are. And if I know that late work is coming to me, I will be able to allot time to grade and respond to it with far greater ease than if it suddenly appears in my inbox.

In a teaching-focused reading group I attended last year, I and the other participants debated the idea of taking off points for late assignments. This is a fairly electric issue-- although in my memory, we appreciated the text's point that punctuality has little to do with mastery of the material, per se, we also expressed an interest in protecting our own time, as grading assignments piecemeal tends to take much longer than doing them all together. Ultimately this conflict is often resolved with a communication compromise: If a student requests an extension in advance of the deadline, the delay does not affect their grade. This resolution promotes respect for the time of both parties, benefiting both. Encouraging students to approach me and, by extension, other instructors when they know they will be absent from an important meeting, need an extension, or have to reschedule an exam could result in a more convenient schedule if one isn't trying to complete two projects at the same time when they could have received an extension for one. It could also result in an improved grade, if it frees a student from trying to plow through the project without careful thought simply to get it in on time. And even if discussion with an instructor does not lead to an extension, it will at least lead to greater clarity on what the instructor's expectations are. And if I know that late work is coming to me, I will be able to allot time to grade and respond to it with far greater ease than if it suddenly appears in my inbox.

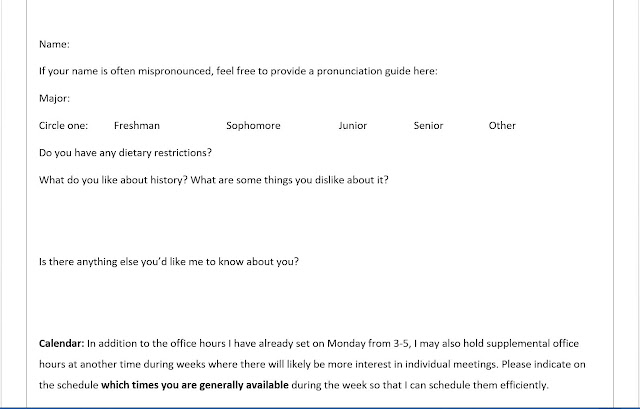

My favorite way to open the door to sustaining practical communication is handing out "first day sheets," an idea I borrowed from one of my favorite former professors at the University of Tulsa. I change it up a bit depending on the course (the "history" question is most often tailored to the specific themes of the course), but below is my basic format.

When I was a student filling out a similar sheet, I thought it seemed like a pleasant way for my professor to get to know a bit about her students. As an instructor, however, I've realized the multiple ways in which the sheet both makes my life easier and communicates messages to students about my approach to the course. First, the practical-- I often use these as a tool to learn names, as they give me a bit of information to attach to each person when I am taking roll or reviewing during the first few weeks. I get some information on what topics or issues the people in that particular semester might be interested in, so that I can emphasize those things. The dietary question and the calendar portion help me to ensure that everyone in the course can be involved in all activities if they so desire: if I bring snacks, I can make sure to provide at least one thing acceptable to each person, and if I schedule extra office hours, I can be sure that at least the majority of students will have the option to attend them.

The sheet also communicates to students that I am willing to learn more about them so as to more effectively help them learn. I tell them they are free to leave anything blank if they wish, so that it is clear that I am not trying to drag information out of them that they do not wish to give. I also provide a space where students can tell me whatever they think I might need to know. Many use this to give little tidbits about their extracurriculars, but I also receive disclosures about minor accommodations they might need, or disclosures about things they find particularly difficult. By opening this line of communication, I try to convey that I am willing to put some effort into making the course accessible and expect the same effort in

One downside of my emphasis on communication with instructors is that, quite simply, all instructors do not encourage this sort of communication and thus it is not a helpful skill for all situations. It is clear from my own interactions with students that some of the ways I would like them to approach me are discouraged by their other instructors. For example: A student approached me wondering if I would excuse her from one class period to attend an interview for a graduate program, offering to provide documentation to prove that her absence was legitimate. When I told her she was free to attend the interview and not worry about the proof, she expressed relief, saying that the professor she had approached first had denied her request, and my class was during the last interview slot available to her. How do I encourage students to communicate honestly with me as adults to solve problems when they are confronted with other instructors who refuse to provide any flexibility? I go back and forth as to the responsibilities I might have to prepare them for reactions different than my own, especially in the case of first-year students.

Students, do you have any memorable experiences about communicating with instructors? Instructors, do you have particular approaches to encouraging communication with students?

|

| First day sheet. You can also access this as a Word document. |

When I was a student filling out a similar sheet, I thought it seemed like a pleasant way for my professor to get to know a bit about her students. As an instructor, however, I've realized the multiple ways in which the sheet both makes my life easier and communicates messages to students about my approach to the course. First, the practical-- I often use these as a tool to learn names, as they give me a bit of information to attach to each person when I am taking roll or reviewing during the first few weeks. I get some information on what topics or issues the people in that particular semester might be interested in, so that I can emphasize those things. The dietary question and the calendar portion help me to ensure that everyone in the course can be involved in all activities if they so desire: if I bring snacks, I can make sure to provide at least one thing acceptable to each person, and if I schedule extra office hours, I can be sure that at least the majority of students will have the option to attend them.

The sheet also communicates to students that I am willing to learn more about them so as to more effectively help them learn. I tell them they are free to leave anything blank if they wish, so that it is clear that I am not trying to drag information out of them that they do not wish to give. I also provide a space where students can tell me whatever they think I might need to know. Many use this to give little tidbits about their extracurriculars, but I also receive disclosures about minor accommodations they might need, or disclosures about things they find particularly difficult. By opening this line of communication, I try to convey that I am willing to put some effort into making the course accessible and expect the same effort in

One downside of my emphasis on communication with instructors is that, quite simply, all instructors do not encourage this sort of communication and thus it is not a helpful skill for all situations. It is clear from my own interactions with students that some of the ways I would like them to approach me are discouraged by their other instructors. For example: A student approached me wondering if I would excuse her from one class period to attend an interview for a graduate program, offering to provide documentation to prove that her absence was legitimate. When I told her she was free to attend the interview and not worry about the proof, she expressed relief, saying that the professor she had approached first had denied her request, and my class was during the last interview slot available to her. How do I encourage students to communicate honestly with me as adults to solve problems when they are confronted with other instructors who refuse to provide any flexibility? I go back and forth as to the responsibilities I might have to prepare them for reactions different than my own, especially in the case of first-year students.

Students, do you have any memorable experiences about communicating with instructors? Instructors, do you have particular approaches to encouraging communication with students?

Related Links:

A few suggestions for instructors on communicating with students, from USC TA Wiki and Inside Higher Ed.

A brief, thoughtful post on how instructors' writing can convey particular meanings to students.

Coming Soon: A new Reacting to Reacting post! Get amped to spend some time with the Greenwich Village Bohemians.

No comments:

Post a Comment